Tax Reform Context

As Washington debates tax reform, “made in the USA” is a being used as a rallying cry by change agents. At the center of the debate is a new White House tax proposal for corporate tax rate reduction. The proposal seeks to lower the corporate rate from the current rate of 35% to a new rate as low as 20%. The proposal’s advocates argue that corporate tax rate reduction will reduce corporate expenses, which will free economic resources for investing in employees, equipment & American innovation. Adversaries of the new corporate tax reduction proposal agree corporate tax reduction will benefit corporations, but suggest the benefits will be limited to executives and business owners rather than the nation as a whole. Reform opposition also points to the growing national debt and suggests a tax rate reduction could reduce total tax revenue collection, a fiscally irresponsible move. Reform advocates suggest mounting debt (over $20 trillion now) is the result of irresponsible spending, pointing to record high tax collection overshadowed by record spending.

Meaningful Conversation

These debates, after clamoring through congress, are recycled by concerned citizens and reach local work meetings and dinner tables. To most seniors, buying products Made in the USA really means something. For us, buying American isn’t just a nationalist argument to win a debate, it is a principle to follow. It means investing in your country, and it means investing in your neighbor. But in this new global economy, it’s getting harder and harder to know how to buy American. You might even wonder if it’s still important to buy something made in the USA. The topic deserves some attention.

So we dug a little deeper in what it means to buy American, and we have mixed feelings.

A Global Marketplace

In the book The Travels of a T-Shirt in the Global Economy (Buy on Amazon), Pietra Rivola describes buying a t-shirt in a shop in Florida. To learn more about how that shirt arrived in a Florida retailer, Rivola researched back in time to when the shirt’s life began. Working backward, she discovers the shirt was shipped to Florida from a Chinese company based in Shanghai. The shirt’s origin takes a twist when the reader discovers the shirt was made from cotton exported from West Texas in a small town called Smyer, home to a cotton farm. This story begs the question, and try to follow this “if an American farmer sells cotton to a Chinese t-shirt manufacturer, and the shirt is then sold to an American wholesaler, an American retailer, and finally to an American consumer, is this an example of buying American?” The answer is (mathematically) more yes than no.

It Gets More Complicated

So if you think this is an isolated example of the complexities of global commerce, consider the following: The largest American auto manufacturers are now Honda and Toyota, two “Japanese” car companies. It turns out these companies make and sell more cars in the United States than any of the big auto companies in Detroit.

Next consider Budweiser, an American icon for beer. Budweiser started in St. Louis and is made in a dozen breweries across the continental United States. Did you know that Budweiser is owned by a Belgian company named InBev? InBev was the outcome of a merger between a Brazilian company formerly named AmBev and a Belguim company named Interbrew. You might be uncomfortable with the idea that Budweiser, a foreign-owned company, is at least as American as Toyota, who is also foreign-owned and also manufactures products in the United States.

Maybe you’d say a company needs to be based in the U.S. to be an American company. And that would be a clever argument, since American companies pay taxes in the U.S. and hire (at least often, but not exclusively hire) Americans for their U.S. facilities. But there are examples of this that will make you scratch your head. Take Apple, for example. Is buying an Apple product that’s designed in California buying American? You might feel differently if you learned the American company’s product were designed in California but made in China. You probably wouldn’t say buying an iPhone is un-American. But, if the standard for “made in the USA” means assembled here, then some Honda cars (made in North Carolina) may be a more American than the Apple iPhone.

No Clear Answer

The only clarity we have is that this is a nuanced issue, with several considerations. First, a product changes forms during its life. Products exist as a design, as raw materials, components, assembled goods, wholesale goods, retail goods & even resold goods. Transformations in value occur at each phase, and in most cases in our global economy, both Americans and foreign nations are involved in this value chain. And second, company ownership is often complex. Some companies were founded in the U.S. and remained owned by Americans. But often, companies have significant foreign ties. If a company is headquartered in the U.S., but its shareholders are all overseas, is that an American company? Surprisingly, there is not always a clear answer for whether a company or product is American made.

For your Consideration

So what does it mean to buy American, exactly? In a nutshell, in the new global economy, “Made in the USA” has been reduced to little more than a marketing slogan. And in a way, we believe that’s sad. Still, technology has brought ideas, labor and resources across borders and in many cases that’s a good thing.

Maybe the best approach to buying American is to decide what Made in the USA means to you. After you’ve set some boundaries, do your research on the companies you choose to buy from.

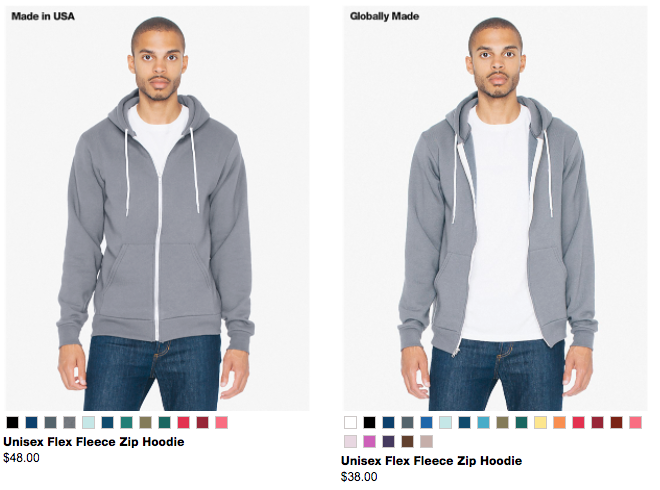

As an exercise, check out the American Apparel online store, with its product example featured below (ironically, the company filed for bankruptcy because it couldn’t control costs).  Regardless of whether or not you like the clothes, ask yourself, “am I willing to spend more for something that’s American, just because?” If your answer is yes, good for you. If your answer is no, maybe that’s OK too because as it turns out… we’re all global consumers now anyway.

Regardless of whether or not you like the clothes, ask yourself, “am I willing to spend more for something that’s American, just because?” If your answer is yes, good for you. If your answer is no, maybe that’s OK too because as it turns out… we’re all global consumers now anyway.